Epidemiology of suicide attempts and self-harm in emergency departments: a report from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) of Korea, 2018–2022

Article information

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a major global public health issue, contributing close to 800,000 deaths every year around the world [1]. Among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, Korea has the highest suicide rate with 24.1 deaths per 100,000 people, which was approximately two times higher than the average of other OECD countries in 2020, and this phenomenon has been going on for more than a decade [2,3].

An episode of suicide attempt or self-harm (intentional self-poisoning or self-injury) is the most important risk factor for eventual suicide [4]. The risk of suicide increases 50 to 100 times within the first 12 months after an episode of self-harm compared to the general population [5–7]. Thus, identifying the demographic characteristics of self-harm and understanding trends and patterns could be helpful in formulating policies for suicide prevention. The emergency department (ED) is often the first place where self-harm patients visit, making the analysis of self-harm patients who present to the ED crucial in this context.

The objective of this study is to determine the demographic characteristics and trends of self-harm and suicide patients who have presented to EDs across Korea over the past 5 years.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Medical Center, Korea (No. NMC-2023-08-094). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

DATA SOURCES

This study used the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) database in Korea. NEDIS is an emergency information network designated by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea, which has been in use since 2003 and is operated by the National Emergency Medical Center (Seoul, Korea). NEDIS includes administrative and clinical information on all patients who have visited all 402 nationwide EDs across the country [8]. The NEDIS data contains patient information including demographics (sex, age, address, and insurance), symptoms (chief complaints and onset), prehospital (emergency medical services [EMS] use and treatment), and ED-hospital (vital signs and level of consciousness at presentation, triage, diagnosis codes based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, disposition, hospital stay after admission, and final clinical outcomes) information. The study population included 5 years of patients who visited EDs for suicide attempts or self-harm from January 2018 to December 2022. A patient who presents at emergency medical facilities nationwide was considered a self-harm or suicide attempter if they met any of the following three conditions: (1) the intention of self-harm or suicide; (2) initial severity classification falls into the suicide attempt, suicidal intent, or suicidal ideation categories under the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS); or (3) discharge diagnosis codes based on the Korean Standard Classification of Disease, X60–X84 (excluding X65).

DEMOGRAPHICS AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PATIENTS

Of a total of 206,409 ED patients, the proportion of adults aged 18 to 64 years was 79.4%. We first divided the population into pediatrics, adults, and the elderly, based on age and then examined their respective characteristics. The total sex distribution was 38.8% male and 61.2% female. However, in the elderly population, unlike pediatrics and adults, there was a higher proportion of male sex, exhibiting a distinctive sex pattern. Most patients visited facilities rated at the level of local centers or higher. Pediatrics mainly arrived as walk-in patients, whereas adults and the elderly frequently utilized EMS services. Disposition was determined within 6 hours of arrival in the ED, but there was a slightly longer delay for the elderly (Table 1).

When categorizing patients by ED facility level, it was observed that patients in local facilities had relatively shorter lengths of stay compared to regional centers, but there were no significant differences in other characteristics (Table 2).

FIVE-YEAR TRENDS IN SUICIDE ATTEMPT OR SELF-HARM BY SEX

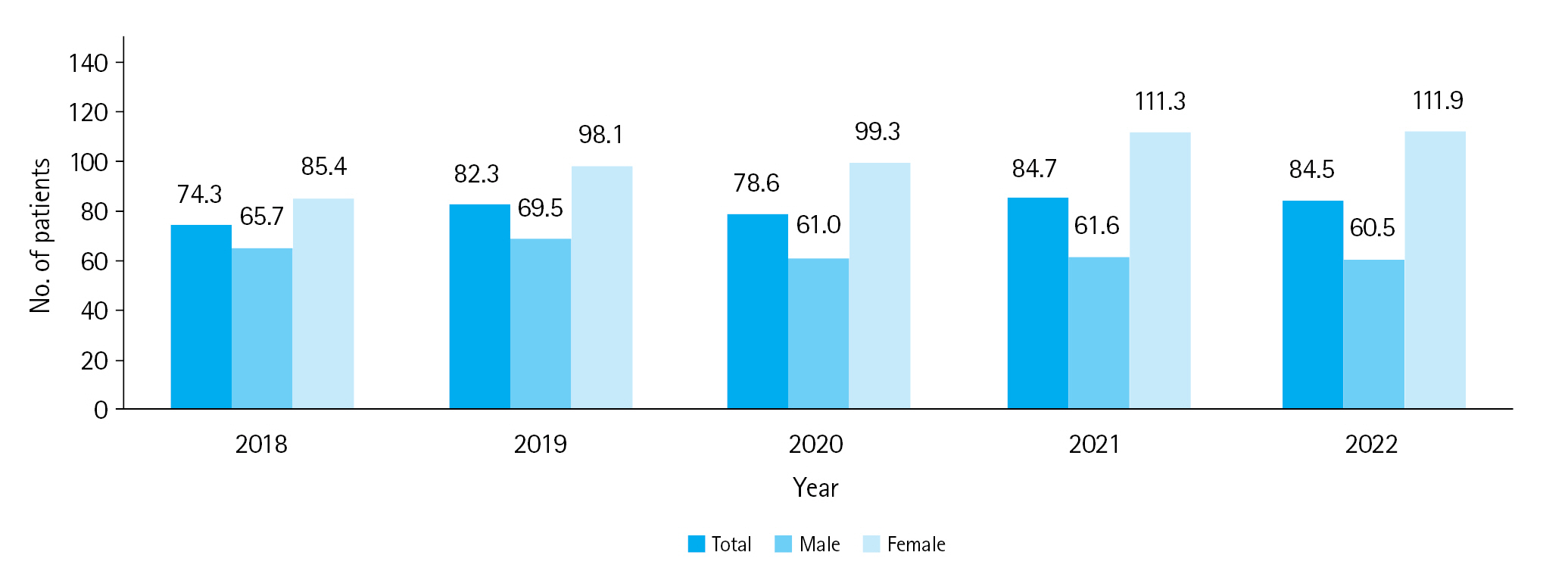

Yearly incidence and mortality rates were examined. Over the 5-year study period, age- and sex- standardized incidence rates per 100,000 population exhibited a consistent upward trend, except in 2020, with a continuous increase observed in women, an approximately 31.0% increase in 2022 compared to 2018 (Fig. 1).

Age- and sex-standardized emergency department visit of suicide attempt and self-harm per 100,000 population.

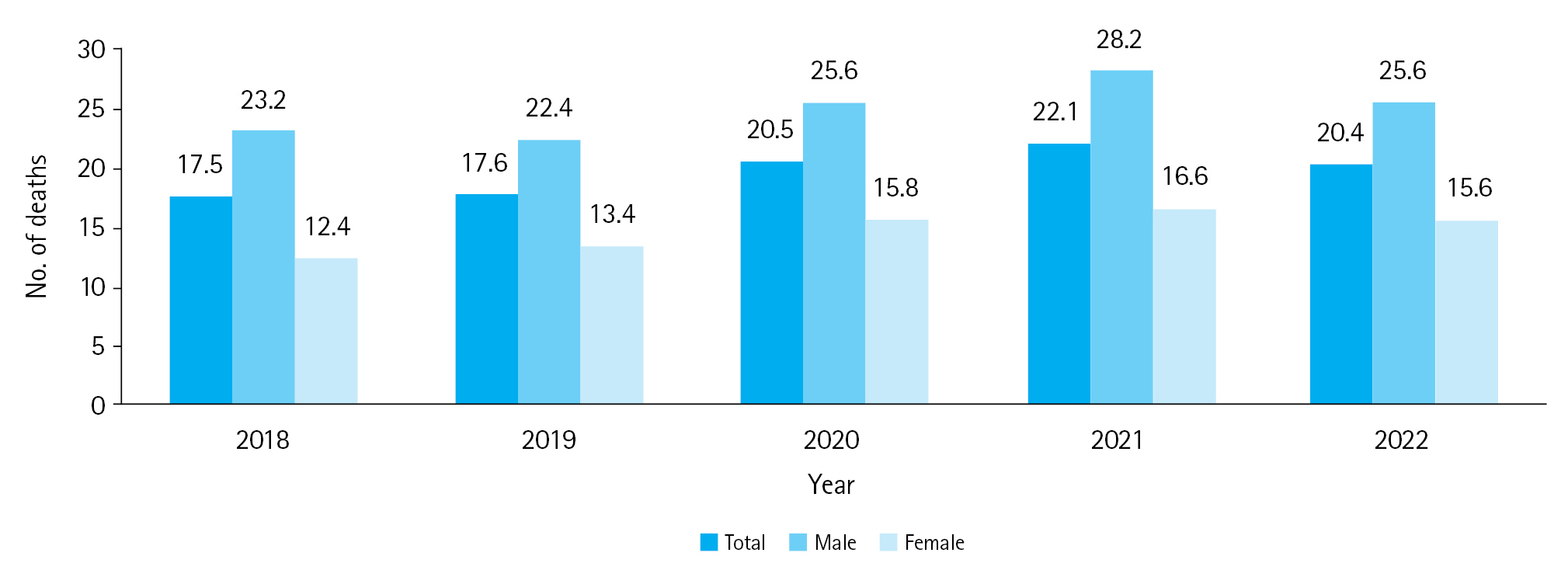

In-hospital mortality rate remained relatively stable throughout the study period (Fig. 2). However, in-hospital mortality rate per 100,000 ED visits has shown an average increase of approximately 20% over the past 3 years compared to the first 2 years before COVID-19. This trend was observed among both men and women, with women exhibiting a higher rate of increase (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

We investigated 5-year NEDIS data to identify the characteristics of patients who presented to the ED due to suicide attempt or self-harm, as well as annual trends over the study period. The results showed distinct sex differences among the age groups where there was a higher proportion of female patients in the pediatric and adult groups, and a higher prevalence of male patients in the elderly group (Table 1). The higher frequency of self-harm in women and the reversal of sex patterns in the elderly have been confirmed not only in our country’s previous research, but also globally. It has also been observed that these sex trends continue even in recent times [2,9,10].

There were no significant differences in demographics or in-hospital characteristics among the types of EDs. However, the number of patients presenting to each type of ED exhibited a substantial difference. The discrepancy may be derived from several reasons that the intention of injury or related KTAS criteria are not mandatory for NEDIS entry in level III EDs. Additionally, even if patients initially presented to a level III ED, severe patients may have been transferred to level I or II EDs. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that critically ill patients were excluded after transfer since their data would have been included in the NEDIS database of level I and II EDs. However, there is a possibility that the number of mild cases that initially presented to level III EDs and were subsequently discharged were underestimated.

When examining the incidence rates of suicide attempt and self-harm per 100,000 population over a 5-year period, there was a significant difference in the contribution of sex. In particular, it was observed that the incidence rate per 100,000 population among women increased significantly, especially after the COVID-19 outbreak. Previous research on self-harm patients in Korea demonstrated similar sexual discrepancies in self-harm patients to this study and also revealed that young women have made a growing contribution to increasing self-harm rates among females over the last few years [11,12]. However, sex-specific in-hospital mortality rates exhibited a reverse trend to the incidence rate. While the in-hospital mortality rate among men showed an overall increase, that for women did not.

Despite sustained national efforts initiated in the early 2000s, Korea's suicide rate has shown no signs of decline. This trend was reaffirmed through the analysis of NEDIS data from the past 5 years, with a notable acceleration in both incidence and mortality rates in the three years following the COVID-19 outbreak. It has been established in previous research that the COVID-19 epidemic, along with lockdowns and economic crises, have significantly impacted high-risk groups for suicide [13,14], resulting in increased suicide attempts and self-harm [15]. Considering the increased mortality associated with suicide attempt and self-harm in the elderly population, these trends could be a burden on society as a whole as we rapidly age into an elderly society. It is essential to examine the characteristics of suicide attempt and self-harm, especially among women and the elderly, and to formulate relevant policies to address this issue.

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: all authors; Data curation: TK, YSR; Methodology: all authors; Project administration: YSR; Visualization: KYJ, TK; Writing–original draft: KYJ; Writing–review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The authors did not receive any financial support for this study.

Data availability

Data of this study are from the National Emergency Medical Center (NEMC; Seoul, Korea) under the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea, which were used under license for the current study. Although the data are not publicly accessible, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request with permission from the NEMC.