AbstractObjectiveTo study the effect of time on shift on the opioid prescribing practices of emergency physicians among patients without chronic opioid use.

MethodsWe analyzed pain-related visits for five painful conditions from 2010 to 2017 at a single academic hospital in Boston. Visits were categorized according to national guidelines as conditions for which opioids are “sometimes indicated” (fracture and renal colic) or “usually not indicated” (headache, low back pain, and fibromyalgia). Using conditional logistic regression with fixed effects for clinicians, we estimated the probability of opioid prescribing for pain-related visits as a function of shift hour at discharge, time of day, and patient-level confounders (age, sex, and pain score).

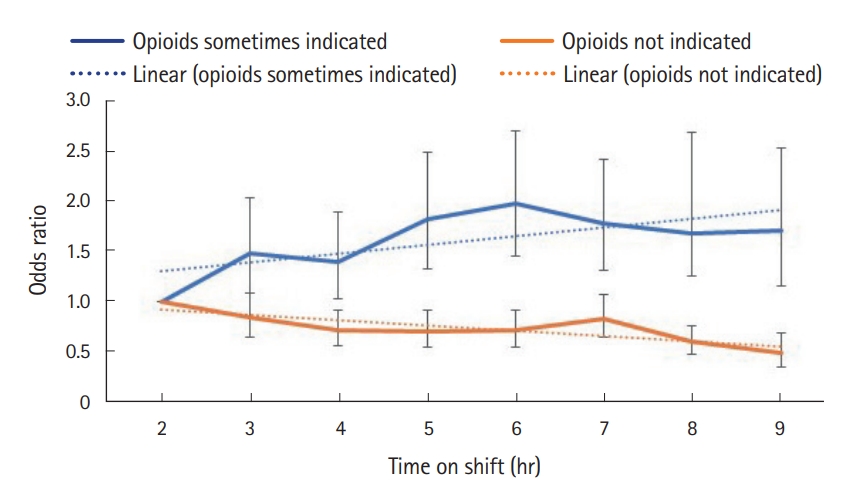

ResultsAmong 16,115 visits for which opioids were sometimes indicated, opioid prescribing increased over the course of a shift (28% in the first hour compared with 40% in the last hour; adjusted odds ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.02–1.10; adjusted P-trend <0.01). However, among visits for which opioids are usually not indicated, relative to the first hour, opioid prescriptions progressively fell (40% in the first hour compared with 23% in the last hour; adjusted odds ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.91–0.96; adjusted P-trend <0.01).

ConclusionAs shift hour progressed, emergency physicians became more likely to prescribe opioids for conditions that are sometimes indicated, and less likely to prescribe opioids for nonindicated conditions. Our study suggests that clinical decision making in the emergency department can be substantially influenced by external factors such as clinician shift hour.

INTRODUCTIONThe opioid epidemic has led to critical self-reflection of when and for whom, to prescribe opioids from the emergency department (ED). Although emergency physicians tend to prescribe small quantities of opioids [1], several studies have shown these prescriptions can still lead to misuse [2,3]. In one analysis, 36% of patients who were discharged from the ED with an opioid prescription self-reported medication misuse at the 30-day follow-up [3].

Primary care physicians have been shown to become more lenient with prescribing antibiotics over the course of a clinic session [4]. More recently, this trend has also been observed in primary care settings for opioid prescriptions [5]. These findings have been attributed to “decision fatigue,” which is the erosion of self-control after making a large number of decisions. Decision fatigue is demonstrated in other fields as well, such as in the justice system, where judges are more likely to deny parole, generally considered the “easier” or “safer” option, later in their session [6]. We sought to evaluate whether prescribing practices for opioids change over the course of an ED shift.

METHODSStudy design and ethics statementThis was a retrospective observational study of de-identified timestamped data. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (No. 2017 P-000593). Witten informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Study settingThis study was conducted in an urban academic ED (Boston, MA, USA) staffed by attending physicians and residents, with approximately 55,000 annual visits. No advanced practice providers were included. Attending physicians and residents worked synchronized shifts, 8 to 9 hours in length. Residents self-assigned to patients according to the electronic rack order once patients entered the department; all patients seen by a resident are staffed by that resident’s supervising attending physician. The final hour of each shift was dedicated to wrap-up, and physicians were not expected to see new patients during that hour, with the expectation that, at the end of a shift, signed-out patients had a clear disposition. Timestamps were automatically recorded by the electronic medical record system, including the time of patient discharge.

Study protocolWe identified visits for five pain-related conditions from 2010 to 2017 among adults without chronic opioid use from our electronic medical records using International Classification of Diseases 9 and 10 billing codes. Chronic opioid use was defined as having an existing prescription for an opioid medication in a patient’s medication list. Participants included in our study were categorized by visit diagnosis as having conditions for which opioids are “sometimes indicated” (fracture and renal colic) or “usually not indicated” (headache, low back pain, and fibromyalgia) according to national guidelines [7].

Our primary outcome was a binary indicator of whether opioids were prescribed at the time of a patient’s discharge from the ED. The quantity and duration of the prescriptions were not captured in our dataset. Pain scores with a 0 to 10 scale were compared among patients for whom opioids were prescribed and not prescribed using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test.

Our main independent variable was the hour of the attending physician’s shift at which a patient was discharged from the ED (e.g., time at which a prescription was signed). This variable, which we call “shift hour,” was calculated as the time from the start of the attending physician’s shift to the time at which a patient was discharged, and it was treated as a categorical variable.

Patient-level information including age, sex, and pain score were recorded on presentation to the ED by nursing triage staff. Patients reported their pain using a previously validated numerical rating scale [8], in which 0 was described as “no pain” and 10 was described as “the worst pain imaginable.” Approximately 5% of our data had missing values for pain score, and these data were excluded from our analysis. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Data are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables and as the numbers with percentages for categorical data. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, while categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson chi-square test.

Using conditional logistic regression, we estimated the multivariable-adjusted probability of opioid prescribing for pain-related visits as a function of shift hour, time of day at discharge, patient-level confounders (age, sex, and pain score), and fixed effects for attending clinicians. Time of day at discharge was chosen as a potential confounder to account for temporal trends in departmental boarding and crowding, which could influence provider decision-making. Conditional logistic regression is a standard approach for analyzing panel data, and it is used when subjects are measured at multiple time points. In our data, subjects (e.g., clinicians) were measured at hourly time points over the course of a shift (e.g., shift hour 1, 2, 3). Using conditional logistic regression with fixed effects by clinician, our results can be interpreted as “within group” (i.e., clinician-specific) effects. As Glober et al. [9] described previously, individual provider patterns of opioid prescribing may vary widely, suggesting the importance of clinician-specific models. Regressions were run separately among patients with conditions for which opioids are sometimes indicated and among those for which opioids were generally not indicated.

In sensitivity analyses, we excluded discharges that took place in the first hour of a physician’s shift, under the assumption that these would be primarily signed-out patients for whom the discharge plan had been formulated by the previous provider. This exclusion accounted for less than 1% of the overall sample and had no effect on our overall conclusions.

RESULTSThere were 16,115 pain-related visits that met our inclusion criteria; 35% resulted in a new opioid prescription. Demographics were similar for patients for whom opioids were prescribed and not prescribed (Table 1). Pain scores were higher for patients who received opioid prescriptions (P<0.01).

Among patients included in our study who had conditions for which opioids are sometimes indicated, the vast majority had a fracture; patients with renal colic accounted for <5% of total cases (Table 2). Patients in our study who had conditions for which opioids are generally not indicated primarily presented with headache or lower back pain; 5% presented for fibromyalgia. The percentage of patients prescribed opioids was higher among conditions for which opioids are sometimes indicated.

Our multivariable-adjusted results are presented in Fig. 1. Among visits for which opioids are sometimes indicated, prescribing increased per hour on shift (adjusted odds ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.02–1.10; P-trend <0.01). However, among visits for which opioids are usually not indicated, opioid prescriptions fell per hour on shift (adjusted odds ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.91–0.96; P-trend <0.01). Unadjusted results are provided in Table 3.

DISCUSSIONWe found that as shift hour progressed, emergency physicians became more likely to prescribe opioids for conditions that are sometimes indicated, such as fractures and renal colic, and less likely to prescribe opioids for nonindicated conditions such as headache, lower back pain, and fibromyalgia. Few studies have examined the effects of visit timing or shift hour on opioid prescribing practices [5], and none have examined these trends among emergency physicians. In the primary-care literature, two recent studies found that primary care physicians were more likely to prescribe both antibiotics [4] and opioids [5] over the course of a clinic session and as appointments run later throughout the day in a linearly increasing pattern.

In our study, we similarly found that for conditions for which opioids are sometimes indicated, specifically fracture and renal colic, emergency physicians became more permissive with prescribing opioids over the course of a shift. We are unable to confirm the exact mechanisms driving these findings as we did not observe physicians’ reasoning or thought processes in our data. However, our findings do support previously proposed hypotheses, including decision fatigue and the desire to move patients through the department more quickly in the face of increasing time pressure. Theoretically, decision fatigue is a term that refers to the cumulative cognitive demand of repeated decision making, which may erode a clinician’s self-control [10]. According to the psychological literature, self-control may be a limited and consumable resource, which degrades over time with continuous self-control effort [10]. As prior studies have suggested, time is needed to explain nonopioid alternatives for pain management and to avoid opioid prescribing risks, making visits longer and requiring physicians to spend precious time dealing with disappointed patients [5]. In a qualitative study of cancer patients with chronic pain and their outpatient clinicians, Satterwhite et al. [11] described opioid prescribing as “time intensive and stress-inducing in the context of short visits.” In the same study, one clinician stated, “I think maybe the over-prescribing [of opioids] is a reflection that we have no time with people.”

Surprisingly, we also found that for conditions for which opioids are generally not indicated, such as headache, lower back pain, and fibromyalgia, emergency physicians appeared to become less permissive with opioid prescribing over the course of a shift. Though unexpected, this was a robust result. We propose several possible explanations for this trend, though further research will be required to investigate these explanations given the limitations of our dataset. One possibility is that, unlike primary care physicians, emergency physicians are unlikely to encounter the same patient in the future, and they may face less pressure to provide prescriptions for nonindicated conditions for the sake of maintaining a patient relationship. Therefore, it may be less mentally taxing for an emergency physician to deny a patient a prescription for opioids compared with a primary care physician. Alternatively, because our data was collected in Massachusetts, where mandatory referencing of prescription drug monitoring programs creates additional effort to look up a patient through a dedicated web portal prior to providing an opioid prescription, emergency physicians may be less willing to prescribe opioids for nonindicated conditions when under mounting time pressure toward the end of a shift. In one prior study, Keister et al. [12] found that emergency physicians are less likely to prescribe opioids when the ED is crowded. Our results are internally consistent, in that time pressure appears to be correlated with a decreased likelihood of providing opioid prescriptions for some patient populations. Ultimately, further research is required to validate our findings in other datasets and study contexts and to investigate possible explanations for our findings.

Our research should be interpreted in the context of the study design, which is a retrospective observational study among patients without chronic opioid use. Each visit to the ED was treated individually. Identifiable data linking visits to specific patients was not included in our dataset. Furthermore, our data were drawn from a single academic tertiary hospital in an urban setting and may not be generalizable to community or county EDs. A limitation of our study is that the quantity and duration of opioid prescriptions was not captured in our dataset, and while this nuance is outside the scope of our current study, it would be an avenue for future research on this topic. We also did not capture pain duration prior to ED visit, effectiveness of prior pain therapies, pain score over the course of the ED visit (only on arrival), or detailed diagnoses such as complex ankle fracture versus small avulsion fracture, which could affect opioid prescribing. Approximately 5% of our patient sample had missing values for pain score, and these patients were excluded from our analysis. Another limitation of our study is the limited sample size for several of the included conditions (renal colic and fibromyalgia), which together made up only <10% of the available data.

The hospital in which our study was conducted is staffed by both attending physicians and residents, and while patient care is ultimately the responsibility of the attending, residents are typically the providers who write the physical prescriptions at discharge. We calculated shift hour based on the attending physician’s shift, which was usually, but not always, the same as the shift hour of the resident seeing the patient (though without any systematic error). Our data did not capture resident identifiers and therefore we were unable to perform analyses according to resident shift hour. However, it is unlikely that the prescriptions written by residents reflected all those and only those that would have been written by the attending. Therefore, the observed trends could be potentially even stronger in an attending-only or community setting.

Many efforts are ongoing to limit opioid prescriptions, including prescription monitoring databases [13] and clinician education curricula [14]. Our study suggests that clinical decision making can be meaningfully influenced by external factors such as clinician shift hour. Standardized decision-making algorithms and shared decision-making tools could help to mitigate the effects of external factors and promote optimal opioid prescribing practices regardless of shift hour. Ultimately, we encourage additional research to investigate the impact of shift timing on emergency physician prescribing practices.

REFERENCES1. Khidir H, Weiner SG. A call for better opioid prescribing training and education. West J Emerg Med 2016; 17:686-9.

2. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:663-73.

3. Beaudoin FL, Straube S, Lopez J, Mello MJ, Baird J. Prescription opioid misuse among ED patients discharged with opioids. Am J Emerg Med 2014; 32:580-5.

4. Linder JA, Doctor JN, Friedberg MW, et al. Time of day and the decision to prescribe antibiotics. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:2029-31.

5. Neprash HT, Barnett ML. Association of primary care clinic appointment time with opioid prescribing. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2:e1910373.

6. Danziger S, Levav J, Avnaim-Pesso L. Extraneous factors in judicial decisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:6889-92.

7. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain: United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016; 65:1-49.

8. Eder SC, Sloan EP, Todd K. Documentation of ED patient pain by nurses and physicians. Am J Emerg Med 2003; 21:253-7.

9. Glober NK, Brown I, Sebok-Syer SS. Examination of physician characteristics in opioid prescribing in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2021; 50:207-10.

10. Muraven M, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol Bull 2000; 126:247-59.

11. Satterwhite S, Knight KR, Miaskowski C, et al. Sources and impact of time pressure on opioid management in the safetynet. J Am Board Fam Med 2019; 32:375-82.

12. Keister LA, Stecher C, Aronson B, McConnell W, Hustedt J, Moody JW. Provider bias in prescribing opioid analgesics: a study of electronic medical records at a hospital emergency department. BMC Public Health 2021; 21:1518.

Fig. 1.Multivariable-adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for prescribing opioids over the course of a shift, by visit type.

Table 1.Patient characteristics for all visits according to whether an opioid was prescribed Table 2.Percentage of patients prescribed opioids, by condition |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||