Outcome and status of postcardiac arrest care in Korea: results from the Korean Hypothermia Network prospective registry

Article information

Abstract

Objective

High-quality intensive care, including targeted temperature management (TTM) for patients with postcardiac arrest syndrome, is a key element for improving outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). We aimed to assess the status of postcardiac arrest syndrome care, including TTM and 6-month survival with neurologically favorable outcomes, after adult OHCA patients were treated with TTM, using data from the Korean Hypothermia Network prospective registry.

Methods

We used the Korean Hypothermia Network prospective registry, a web-based multicenter registry that includes data from 22 participating hospitals throughout the Republic of Korea. Adult comatose OHCA survivors treated with TTM between October 2015 and December 2018 were included. The primary outcome was neurological outcome at 6 months.

Results

Of the 1,354 registered OHCA survivors treated with TTM, 550 (40.6%) survived 6 months, and 413 (30.5%) had good neurological outcomes. We identified 839 (62.0%) patients with preClinsumed cardiac etiology. A total of 937 (69.2%) collapses were witnessed, shockable rhythms were demonstrated in 482 (35.6%) patients, and 421 (31.1%) patients arrived at the emergency department with prehospital return of spontaneous circulation. The most common target temperature was 33°C, and the most common target duration was 24 hours.

Conclusion

The survival and good neurologic outcome rates of this prospective registry show great improvements compared with those of an earlier registry. While the optimal target temperature and duration are still unknown, the most common target temperature was 33°C, and the most common target duration was 24 hours.

INTRODUCTION

Despite recent advancements in critical care, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is still one of the major causes of death in many countries [1-3]. High-quality intensive care, including targeted temperature management (TTM) for patients with postcardiac arrest syndrome (PCAS), is a key element for improving outcomes after OHCA [1,4,5]. TTM is known to improve survival and neurologic outcomes after OHCA [6-9], and several other postcardiac arrest treatment approaches such as emergency coronary angiography (CAG), hemodynamic optimization, ventilator management, and prognostication may also impact patient outcomes [10-19].

Cardiac arrest etiology and quality of postcardiac arrest care, including TTM, as well as outcomes after OHCA differ between countries [20]. It is therefore important to identify the current status of PCAS care in Korea in order to make recommendations that are suitable for the country’s specific circumstances. The Korean Hypothermia Network (KORHN) investigators previously published retrospective, multicenter, observational studies on postcardiac arrest care quality and outcomes in patients treated with TTM between January 2007 and December 2012 [21]. Since then, however, the guidelines have been updated, resulting in changes in TTM treatment, and the retrospective data at the time were based on limited research. The KORHN multicenter clinical research consortium for TTM in South Korea, founded in 2010, therefore launched a multicenter, prospective registry of OHCA patients, and enrolled approximately 10,000 such patients from 22 participating institutions between October 2015 and December 2018.

Using this database, we aimed to assess the current status of PCAS care in Korea, including TTM and 6-month survival with neurologically favorable outcomes, after adult OHCA patients were treated with TTM.

METHODS

Study design and participation

This study was a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study. Data were collected from the KORHN prospective (KORHN-PRO) registry, a web-based registry of OHCA patients treated with TTM that aimed to improve postcardiac arrest care quality and outcomes. Adult (≥18 years) comatose patients treated with TTM between October 2015 and December 2018 were included.

Each investigator, from one of the 22 teaching hospitals that intended to be included in this registry, was required to fill out the participation form available on the website of the KORHNPRO registry (http://pro.korhn.or.kr/). A registry manual was created. Investigators were repeatedly educated every 3 months, and researchers were asked to share the queries and others that occurred by attending the education every time. Five clinical research associates monitored the data and improved their quality by sending queries to all investigators, and one data manager eventually examined the data and decided whether records could be accepted or needed revision.

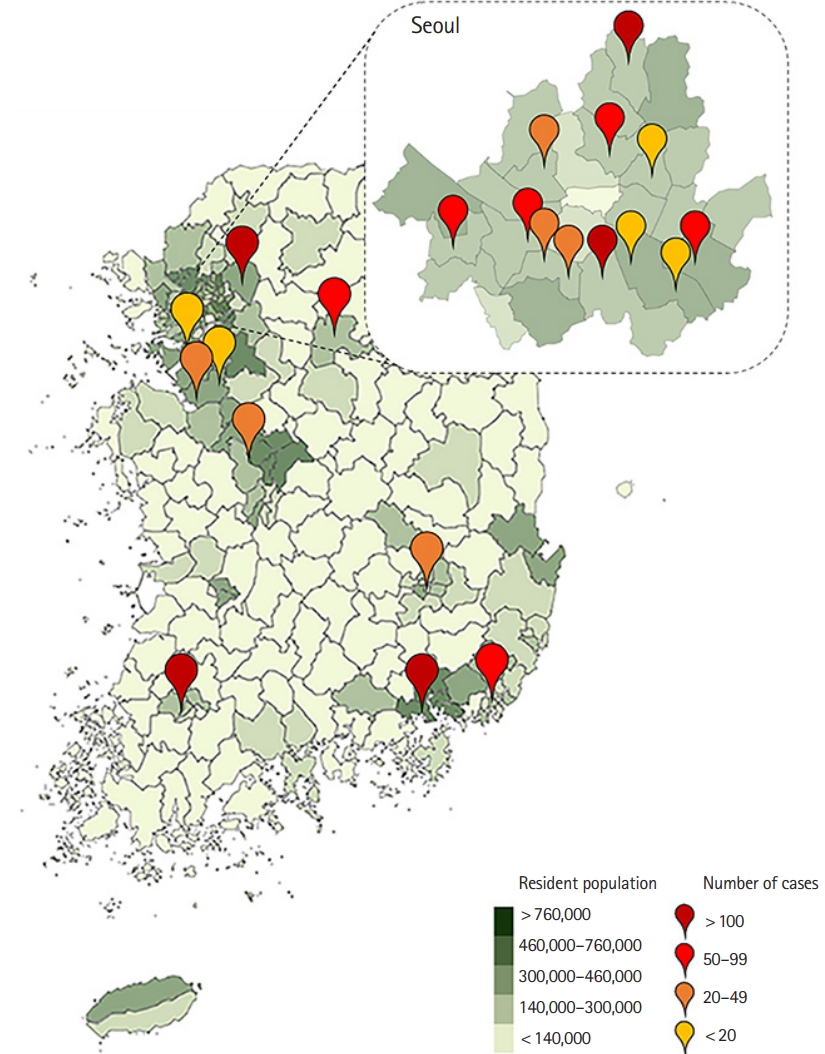

The participating institutions (n=22) were evenly distributed throughout the entire country (Fig. 1). The study design and plan, including the informed consent form, were approved by the institutional review boards of all participating hospitals and registered on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (NCT02827422). In accordance with national requirements and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ legal surrogates rather than from the patients themselves.

Data collection

The KORHN-PRO registry collected a large amount of information, consisting of 136 variables with 839 datasets.

Baseline patient information

The date and place of cardiac arrest, hospital visit type (transferred or not), age, sex, height, weight, prearrest Glasgow-Pittsburgh Cerebral Performance Category (CPC)/modified Rankin scale (mRS) score, and comorbidities (coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, lung disease, renal impairment, liver cirrhosis, and malignancy) were documented.

Resuscitation variables

Cardiac arrest etiology was dichotomized as medical or nonmedical; medical causes included cases in which the cardiac arrest was presumed to be of cardiac origin or due to other medical causes and those in which there was no obvious cause of cardiac arrest. The initial arrest rhythm was defined as a shockable rhythm when the first monitored rhythm was found to be ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. Other resuscitation variables were as follows: witness of collapse, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) status (ROSC after hospital arrival, ROSC before hospital arrival, no ROSC), mechanical chest compression, epinephrine or vasopressin dose, end tidal carbon dioxide concentration during resuscitation, and time from collapse to ROSC.

TTM

The following TTM data of patients were prospectively collected: target temperature, target duration, temperature monitoring site, hourly body temperature from ROSC to 96 hours, TTM methods (blanket, ice bag, adhesive pad, garment, fan, linen, cold saline, intravascular catheter, lavage, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), time from ROSC to start of TTM, time from start of TTM to achieving the target temperature, maintenance duration, rewarming duration, controlled normothermia, and duration and maximal temperature after rewarming for 3 days.

In-hospital data including treatments

Hemodynamic parameters, shock after ROSC (a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg for >30 minutes, or the need for supportive measures to maintain a blood pressure of 90 mmHg), the Glasgow Coma Scale score after ROSC, arterial blood gases, 12-lead electrocardiography, and serum troponin levels were measured immediately after ROSC. The lowest hypoxic index on the day, the cardiovascular sequential organ failure assessment score, serum creatinine levels, platelet counts, bilirubin levels, the patient’s fluid balance, and their neurologic status (i.e., their Glasgow Coma Scale score, pupillary light reflex, and corneal reflex) were evaluated daily up to 7 days after ROSC. Adverse events within 7 days after ROSC (seizures, bleeding, infections, sepsis, pneumonia, hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypoglycemia [blood glucose <60 mg/dL], sustained hyperglycemia [blood glucose >180 mg/dL for >4 hours], tachycardia [>130/min], and bradycardia [<40/min]) and rearrest events were documented. The registry contained data on advanced cardiac treatments (e.g., CAG, percutaneous coronary intervention, results of CAG, coronary artery bypass graft, extracorporeal bypass, intra-aortic balloon pump, use of thrombolytics, electrophysiology study, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator insertion, and pacemaker insertion), echocardiography, regional wall motion abnormalities, time from ROSC to CAG, and continuous renal replacement therapy.

Outcomes and outcome prediction modality

The researchers prospectively recorded whether there were any decisions regarding limitations of active treatments during hospital care (i.e., withdrawal of life sustaining therapy, whether patients underwent essential diagnostic testing, or whether do not attempt CPR orders were in place). Neurologic outcomes were investigated by the researchers at each hospital, and assessed at discharge as well as at 1 and 6 months after cardiac arrest. The KORHN protocol recommends a minimalist approach when assigning the Glasgow-Pittsburgh CPC score that is based on four simple questions, and the researchers contacted either surviving discharged patients or their relatives to calculate the score. Follow-up was recommended by face-to-face or telephone interviews.

The various modalities used for outcome prediction were also prospectively collected and included the following: brain computed tomography (CT), brain magnetic resonance imaging, serum neuron-specific enolase every 24 hours for 72 hours, median nerve somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs), and conventional electroencephalogram (EEG).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the neurologic outcome assessed using the CPC score 6 months after cardiac arrest according to the recommendations for outcome assessments in comatose cardiac arrest survivors; it was recorded as CPC 1 (good performance), CPC 2 (moderate disability), CPC 3 (severe disability), CPC 4 (vegetative state), or CPC 5 (brain death or death). Neurological outcomes were then dichotomized into good (CPC 1 or 2) or poor (CPC 3 to 5) [22,23]. Additionally, we used the mRS to assess neurological outcomes, with an mRS score of 0 to 3 being considered a good outcome and an mRS score of 4 to 6 a poor outcome (with an mRS score of 6 indicating death) [22,23].

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed using chi square tests or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. We tested the distributions of continuous variables for normality using visual inspection and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data are expressed as means and standard deviations and assessed using Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed data are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges and assessed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic and baseline characteristics

During the study period, a total of 10,258 patients with OHCA were initially screened for the registration. Of those, 1,373 patients were treated with TTM and thus included in the KORHN-PRO registry. A total of 1,354 patients (98.6%) with complete data including the 6-month neurologic outcomes were finally included in this study.

The patients’ clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 961 patients (71.0%) were male, and the mean age was 58 years. Patients with a good neurological outcome were significantly more likely to be male and younger (P<0.001). Hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity. Patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus were more likely to have a poor neurological outcome. There were 839 patients (62.0%) with presumed cardiac etiology. A total of 937 collapses (69.2%) were witnessed, and 834 patients (61.6%) received bystander CPR. Shockable rhythms were identified in 482 patients (35.6%), and 421 (31.1%) patients arrived at the ED with prehospital ROSC. Good neurologic outcomes were associated with witness of collapse, bystander CPR, shockable rhythms, shorter times from collapse to ROSC, and prehospital ROSC (P<0.001).

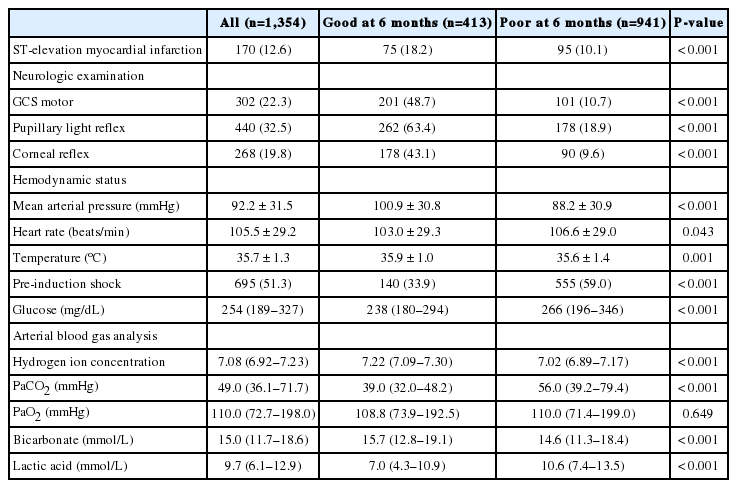

Clinical findings immediately after ROSC

Immediately after ROSC, 170 (12.6%) patients showed ST elevation on 12-lead electrocardiography (Table 2). Patients with a good neurologic outcome had a significantly higher mean arterial pressure than patients with a poor neurologic outcome. Preinduction shock was more common in patients with a poor neurologic outcome than in those with a good neurologic outcome (P<0.001). The poor neurologic outcome group had higher glucose and elevated lactic acid levels than the good neurologic outcome group (P<0.001).

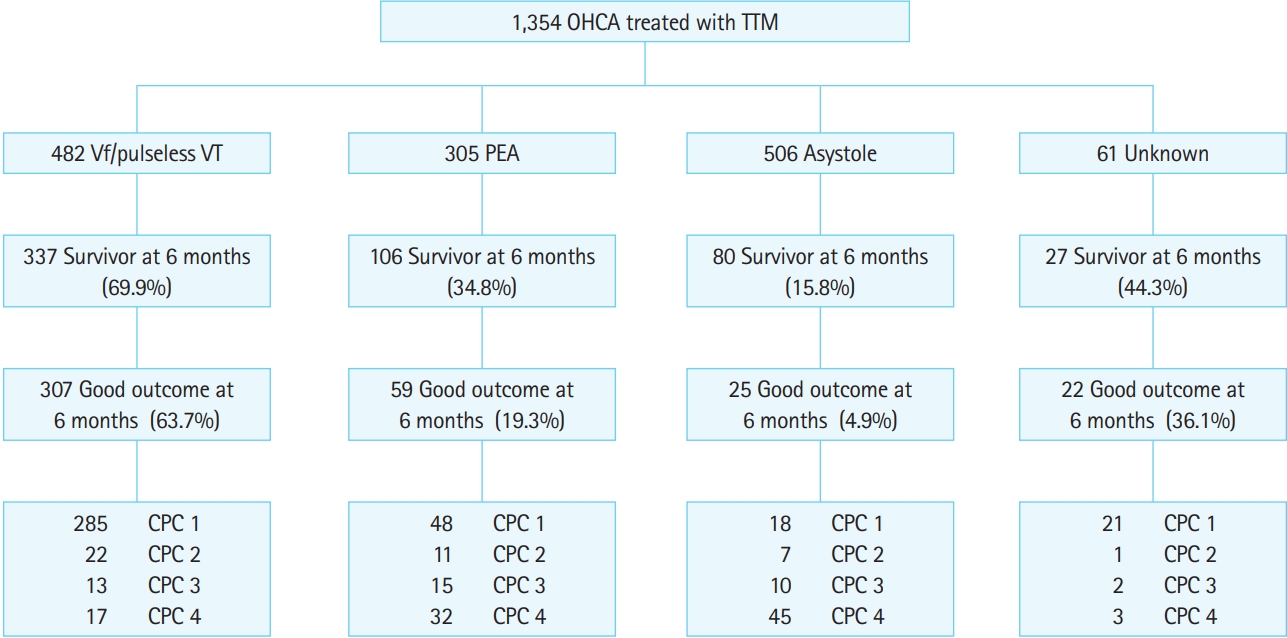

Neurological outcome and survival according to the first monitored rhythm

Fig. 2 shows an overview of the registered patients. Of the 1,354 total patients, 550 (40.6%) survived 6 months, and 413 (30.5%) had good neurologic outcomes at 6 months. Of the 482 patients who experienced OHCA with shockable rhythms, 337 (69.9%) survived 6 months, and 307 (63.7%) had good neurologic outcomes at 6 months.

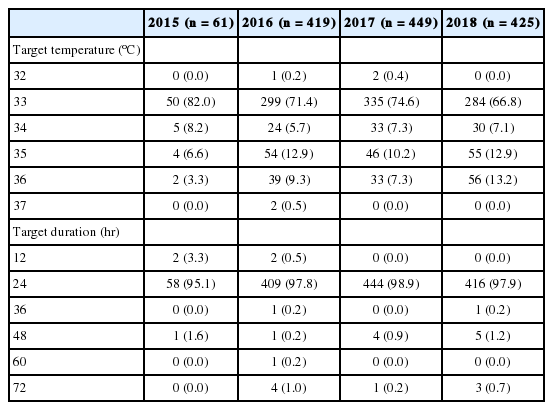

TTM practices and complications

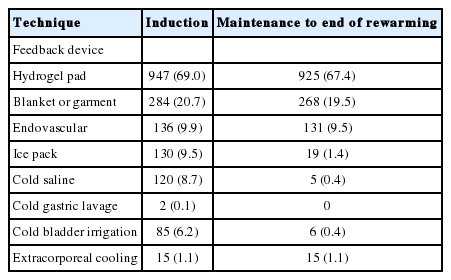

The most common target temperature was 33°C, with an annual increase in the proportion of target temperatures above 35°C (Table 3). The most common target duration was 24 hours, and most patients (89.7%) were actively rewarmed at a rate of 0.25°C/hr (54.8%). After rewarming, 736 patients (53.6%) maintained normothermia for an average of 32.6 hours. The hydrogel pad was most frequently (69%) used for induction, and 925 (67.4%) patients used it for maintenance and rewarming (Table 4).

Table 5 shows incidences of complications during TTM. Seizures, bleeding, sepsis, hypoglycemia, sustained hyperglycemia, and rearrest were significantly more frequent in patients with poor neurologic outcomes than in those with good neurologic outcomes.

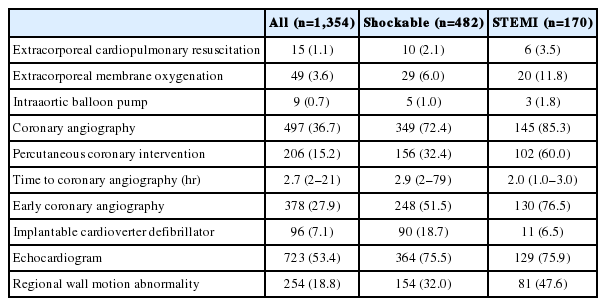

Cardiac care and circulatory supportive therapy

Table 6 shows the use of cardiac care after ROSC. CAG was performed in 497 patients (36.7%), and percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 206 patients (15.2%). CAG was performed in 349 (72.4%) of 482 patients with shockable rhythms and in 145 (85.3%) of 170 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The median time from ROSC to CAG was 2.7 hours, and 378 (76.1%) patients underwent CAG within 24 hours.

Modalities for outcome prediction

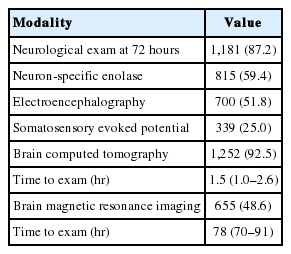

Neurologic examinations 72 hours after ROSC were performed in 1,181 (87.2%) patients, and serum neuron-specific enolase was checked in 815 (59.4%) patients. SSEP was performed in 339 and EEG in 700 patients. Most patients (92.5%) underwent brain CT examinations, and the median time to exam was 1.5 hours. A total of 655 patients underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging examinations, and the median time to exam was 78 hours for predicting neurologic outcome after OHCA (Table 7).

DISCUSSION

The KORHN committee launched a multicenter, prospective registry that focuses on OHCA patients treated with TTM since October 2015. This report briefly describes the characteristics and outcomes of the registry from October 2015 to December 2018. Of the 1,354 registered OHCA survivors treated with TTM, 550 (40.6%) survived 6 months, and 413 (30.5%) had good neurological outcomes.

This study has several strengths. First, this is the first prospective registry involving multiple centers in Korea. Second, 98.6% of all enrolled patients provided data on the primary outcome of our study, that is, neurologic outcome at 6 months after cardiac arrest.

The good neurologic outcome rate of all patients was 30.5%, and the good neurologic outcome rate of patients with initial shockable rhythms was 63.7%. In an earlier TTM trial, 46% of patients with good neurologic outcomes were in the 33°C group and 48% in the 36°C group [8]. However, as this earlier trial did not report rates of good neurologic outcome at 6 months according to initial rhythm, no direct comparison with our registry is possible. In a recently published Time-differentiated therapeutic hypothermia (TTH) 48 trial, the rate of good neurologic outcomes at 6 months was 64% in the 24-hour group and 69% in the 48-hour group [24]. This means that, in the current study, the proportion of patients with an initial shockable rhythm was lower than the same proportion reported in earlier European trials, such as the just mentioned TTM and TTH 48 trials; however, our good outcome rate is similar to those of earlier reports.

In our prospective registry, the most common target temperature was 33°C, and the most common target duration was 24 hours. Although the optimal target temperature and duration are still unknown, many guidelines recommend a target temperature of 32°C to 36°C and a minimum target duration of 24 hours [1,5]. In the United States, the rate of TTM applications has decreased by more than 6% since the publication of the TTM trial [24]. The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society reported that the lowest average temperature of PCAS patients in the first 24 hours in the ICU rose after publication of the TTM trial, and that this change was associated with an increased frequency of fever and a tendency toward an increase in mortality [25]. In the Korean prospective registry, although a target temperature of 33°C was the most common, the proportion of target temperatures of 33°C has been decreasing over the years. However, the current study did not reveal a relationship between the change in target temperature and outcomes. Further research is needed to expand on these findings.

CAG was performed in 497 patients (36.7%), and emergency CAG, which was defined as CAG performed within 24 hours after ROSC, was performed in 378 patients (27.9%). The median time from ROSC to CAG was 2.7 hours, and 378 (76.1%) patients underwent CAG within 24 hours. The TTH 48 trial reported that emergency CAG was performed in 82.6% of patients [24]. Although there was a difference in the initial shockable rhythm rates between the TTH 48 trial and the KORHN-PRO registry, our study shows that even for ST-elevation myocardial infarction cases, the emergency CAG rate was 76.5%; there is thus room for improvement in PCAS care. Additionally, it will be necessary to study the effect of emergency CAG on the Korean population.

Brain CT was the most frequently used modality (92.5%) for outcome prediction and SSEP the least frequently performed, at a rate of 25%. According to one survey from the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, EEG is the most common tool in routine clinical practice, with intermittent EEG, brain CT, and SSEP being considered the most useful tools for assessing prognosis after cardiac arrest [26]. Future studies using the KORHN-PRO registry data will reveal the associations between outcome predictors and prognosis after cardiac arrest.

Our study has several limitations. First, the KORHN-PRO registry included only patients with OHCA who were treated with TTM. Therefore, we were not able to assess the ratio of TTM applications, the total OHCA survival rate, or the effectiveness of TTM. Second, some missing data in the KORHN-PRO registry, in spite of the data manager and clinical research associates monitoring the data and giving feedback to the researchers, might have affected the results. Third, most of the included facilities are teaching or university-affiliated hospitals located within the nation’s capital region. Therefore, a selection bias could not be avoided.

In summary, of the 1,354 OHCA survivors treated with TTM, 550 (40.6%) survived 6 months, and 413 (30.5%) had good neurologic outcomes at 6 months. The most common target temperature was 33°C, and the most common target duration was 24 hours. CAG was performed in 497 patients (36.7%), and emergency CAG, which was defined as CAG performed within 24 hours after ROSC, was performed in 378 patients (27.9%).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

Article information Continued

Notes

Capsule Summary

What is already known

High-quality intensive care, including targeted temperature management (TTM) for patients with postcardiac arrest syndrome, is a key element for improving outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). Several studies have reported the outcome and status of postcardiac arrest care, including TTM, in their own countries.

What is new in the current study

Of the 1,354 total out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors treated with TTM, 413(30.5%) had good neurologic outcomes at 6 months. The most common target temperature and duration were 33°C and 24 hours. This is the first report from a large-scale multicentered prospective registry in Korea.