AbstractA scoping review was conducted to identify, map, and analyze international evidence from studies investigating the prevalence of community cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training. We searched major bibliographic databases and grey literature for original studies evaluating the prevalence of CPR training in the general population. Studies published from January 2000 to October 2020 were included without language or publication type restrictions. Seventy-three eligible papers reported a total of 61 population-based surveys conducted in 29 countries. More than three-fourths of the surveys were conducted in countries with high-income economies, and none in low-income countries. Over half of the surveys were at a subnational level. Globally, the proportion of laypeople trained in CPR varied greatly (median, 40%). For high-income countries, the median percentage was twice as high as that of upper middle-income countries (50% vs. 23%). The studies used heterogeneous survey methods and reporting patterns. Key methodological aspects were frequently not described. In summary, few studies have assessed CPR training prevalence among the general public. The rates of resuscitation training for the vast majority of countries remain unknown. High heterogeneity of studies precludes a reliable interpretation of the research. International Utstein-style consensus guidelines are needed to inform future research and reporting of public resuscitation training worldwide.

INTRODUCTIONOut-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major public health problem with global levels of survival below 10% to date [1]. Evidence suggests that survival is more likely among OHCA victims who receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) from laypeople [1,2]. However, rates of CPR by laypeople remain poor in many countries [3,4].

Lack of sufficient knowledge and skills is known to be one of the predominant reasons that impede laypeople’s readiness to attempt resuscitation [5,6]. It is recognized internationally that effective training of laypeople in CPR is essential to increase the number of people willing and able to provide help in a real-life emergency and to improve survival after OHCA [7]. In order to prioritize and inform training interventions in a community, it is important to understand existing practices of CPR education.

Surveys of the general public help to determine the prevalence rates of CPR training, laypeople’s perceptions, and the barriers for resuscitation education. These provide relevant information for developing and guiding CPR training programs and campaigns [8,9]. Without this knowledge, it is difficult to make reasonable improvements to promote CPR by laypeople. While a number of observational studies have been carried out worldwide to investigate the prevalence of CPR training among the general public, no research has been done yet to identify, map, and analyze the available evidence.

We conducted a global scoping review of studies reporting the prevalence of CPR training in the general population that was published in the last 20 years. The factors associated with being trained in CPR, willingness to be trained, most common sources of such training, and barriers for CPR training were also reviewed.

METHODSThis scoping review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) [10]. The protocol for this review was not preregistered.

Eligibility criteriaAll original studies were considered to be eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) reporting prevalence of CPR training (percentage of people ever being trained in CPR) within a sample drawn from the general population in a particular geographic area and (2) published between January 2000 and mid-October 2020. There were no restrictions for publication type or language.

We excluded studies: (1) reporting prevalence of CPR training for selected categories of the public (rather than the general public), e.g., for particular occupations (medical practitioners, teachers, students, etc.), participants of training events, patients or visitors to medical facilities, specific age groups (e.g., youth, elderly); (2) where a target population, number of participants or study geography were not defined clearly; and (3) reporting prevalence of first aid training in general without specifying rates of CPR training. Studies reporting relevant data for the general public excluding people with medical background were considered to be eligible.

Information sources and search strategyWe systematically searched Embase, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, and relevant grey literature (Google Scholar). A search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table 1. Considering the limited functionality of the advanced search in Google Scholar, we used a simplified search request (resuscitation AND training AND survey) and analyzed 1,000 references which we ranked in relevance. Reference lists of included publications were also manually searched for eligible studies.

Study selection and data collectionThree researchers were responsible for the study selection and data collection process. Two of them screened and extracted the data. In cases of disagreement, a third opinion was sought to achieve consensus.

Titles, abstracts, and keywords of all identified studies were screened, and records of potentially eligible papers were collected using Zotero reference management software. After removing duplicates, the full texts of all potentially eligible papers were obtained and reviewed for eligibility. For non-English papers, the eligibility assessment and data extraction were limited to the contents of English-language abstracts and tables.

The following data were extracted from eligible publications using a predesigned and pilot-tested table: (1) characteristics of the study and participants (including year, country, and geographic coverage of the survey, method of survey administration, method of sampling, number, and age of participants, sample size justification [yes/no], response rate); (2) prevalence of CPR training (percentage of ever trained and percentages of trained within previous 1 year, 2 years, 5 years, or over 5 years out of ever trained); (3) percentage of those willing to be trained in CPR; (4) respondents’ characteristics confirmed to be associated with being trained in CPR; (5) sources of CPR training (with percentage of participants reporting a source); and (6) reasons for not being trained in CPR (with percentage of participants reporting a reason). Considering the high between-study variability in the number and kind of reported sources of training and the reasons for not being trained, data on the three commonest sources/reasons were collected.

In cases where relevant data in percentages (e.g., prevalence of CPR training or response rate) were not reported in a paper, but corresponding numerical data were available, the respective percentage values were calculated by the researchers. Where prevalence rates of CPR training by the timing of last training (e.g., within last year) were presented in publications as calculated out of all survey respondents, respective values were recounted to percentages out of persons ever trained in CPR for conformity. Where a paper reported two or more surveys conducted in distinct study periods or in different countries, the surveys were considered as stand-alone studies. In cases where both a conference abstract and a journal article described the same study, and where discrepancies in data were found between the publications, the data from the journal article were considered to be preferential. Where discrepancies were found between the two articles, the data from the latest paper were considered preferential.

Quality assessmentTo maximize the scope, this review examined all types of publications, including conference abstracts, where methods were not described in detail. The broad inclusion criteria, as well as the large heterogeneity of the included studies, prevented us from performing a formal quality assessment. However, the relevant characteristics of the methodological quality of the studies (primarily as concerns completeness of the description of the methods in journal articles), were considered and analyzed.

RESULTSAfter excluding irrelevant records and duplicates 118 full texts were retrieved and assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1). The final analysis included 73 papers: 53 articles, 18 conference abstracts, one short communication, and one dissertation abstract. Out of nine potentially eligible non-English papers, four articles were included (one Icelandic and three Korean).

Characteristics of the studiesEligible papers described a total of 61 studies (cross-sectional population-based surveys) conducted between 1997 and 2019, reporting data on the prevalence of CPR training among the general public in 29 countries. The details of the included studies are provided in Supplementary Table 2. One paper presented the results of surveys conducted in two countries (China and India) [11], while other papers described single-country surveys.

The distribution of the studies by global regions, subregions, and countries is shown in Fig. 2. The countries represent 14.1% of the 206 world’s sovereign states and 14.5% of the 193 member states of the United Nations [12]. According to the World Bank’s economic classification [13], the surveys involved populations of 25.3% (21/83) countries with high-income economies, 10.7% (6/56) countries with upper middle-income economies (Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Russia, and Turkey), 4.0% (2/50) countries with lower middle-income economies (Ghana and India), and 0% (0/29) countries with low-income economies. Of the studies 39.3% (24/61) were conducted at a national level, 60.7% (n=37) at a subnational level (Supplementary Table 3) [5,6,8,9,11,14-81]. Nation-wide studies were carried out in 19 (65.5%) of the 29 countries reviewed. The number of studies per country varied from 1 to 8.

Regarding sampling methods, 55.7% (n=34) of the studies utilized a probability sample and 36.1% (22) used a nonprobability sample. For 8.2% (5) of the studies, the sample design was not specified (one conference abstract, two abstracts of non-English articles, and two full-text articles). Probability sample designs included a stratified random sample (n=18), a simple random sample (8), a probability sample with quotas (3), a systematic random sample (2), and a random sample of unspecified type (3). Nonprobability sampling methods included a convenience sample (12), a quota sample (7), a voluntary response sample (2) and a snowball sample (1).

The number of survey respondents varied from 303 to 228,921 (median [interquartile range, IQR], 1,007 [566.5–2,077.0]), national studies 428 to 228,921, and subnational studies 303 to 10,048. Out of a total number of 428,340 respondents, 53.4% (228,921) were participants in the nation-wide survey from South Korea [46]. Sample size justification was provided in 30.6% (15/49) of the English language articles.

Sampling criteria by age included: >12 years old (n=1), >14 (n=1), >15 (n=1), >16 (n=5), >17 (n=2), >18 (n=21), >19 (n=7), >20 (n=1), >30 (n=1), 15–64 (n=2), 15–79 (n=1), 16–75 (n=1), 18–69 (n=1), 18–79 (n=1), 18–89 years old (n=1), adults (n=4), age not limited (n=2); or age criteria were not specified (n=8). Seven (11.5%) surveys excluded persons with medical background or medical education.

As regards methods for gathering data, the studies utilized a telephone survey (n=21, 34.4%), a face-to-face interview (n=17, 27.9%), a self-completing questionnaire (n=11, 18.0%) and an online survey (n=6, 9.8%). For six studies (9.8%) the method of gathering survey data was not detailed (stated as “interview,” “survey,” or “questionnaire survey”). Of the surveys 24.6% (n=15) were carried out in public places (gatherings), 18.0% (n=11) were interviews conducted in households. Out of the six online surveys, five questioned laypeople interested/registered to participate in surveys (online survey panelists) and one involved users of online social networks.

The response rates were reported or calculable from available data for 41.0% (n=25) of the studies. The response rates ranged from 30% to 95% (median [IQR], 52 [43.0–64.0]), telephone surveys 30% to 81% (n=15), face-to-face interviews 47% to 95% (n=4), questionnaire self-completion 50% to 87% (n=5), and online surveys 58% (n=1).

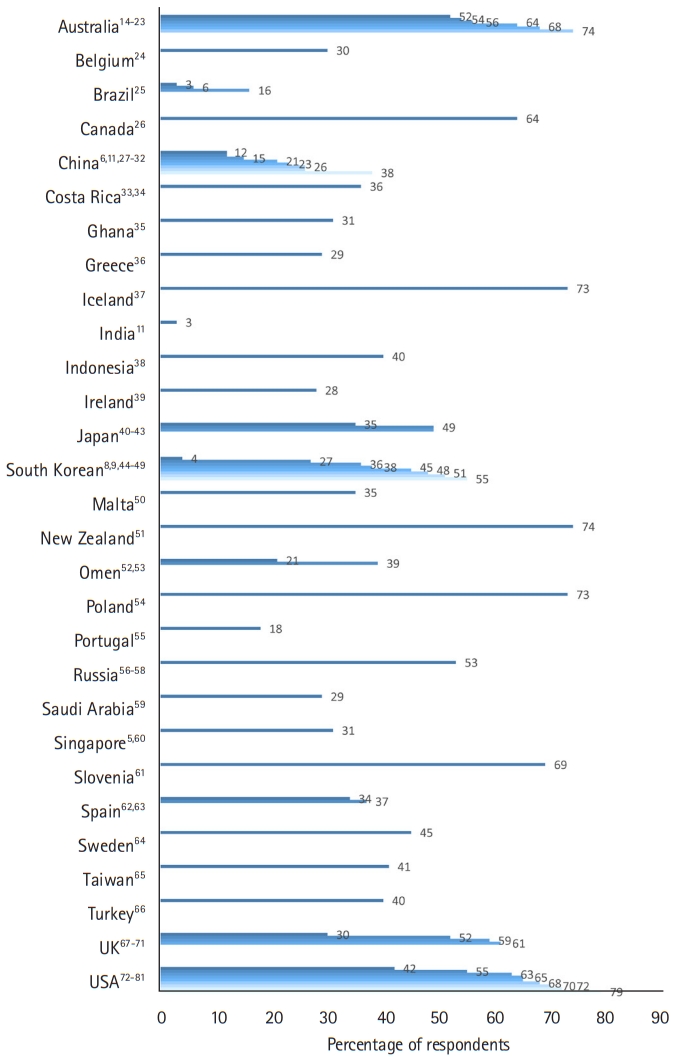

Prevalence of CPR trainingThe proportion of laypeople ever being trained in CPR varied from 3% to 79% globally (median [IQR], 40 [28.5–60.0]) (Fig. 3) [5,6,8,9,11,14-81], from 18% to 73% based on the national studies (39.5 [30.3–58.3]), and from 3% to 79% according to the subnational studies (40 [24.5–62.0]) (Supplementary Table 3). By the country’s income level, the range of CPR training rates were distributed as follows: high income 4% to 79% (median [IQR], 50 [35.0–64.8]), upper middle income 3% to 53% (23 [12.0–38.0]), and lower middle income 3% to 31% (17 [not calculable]).

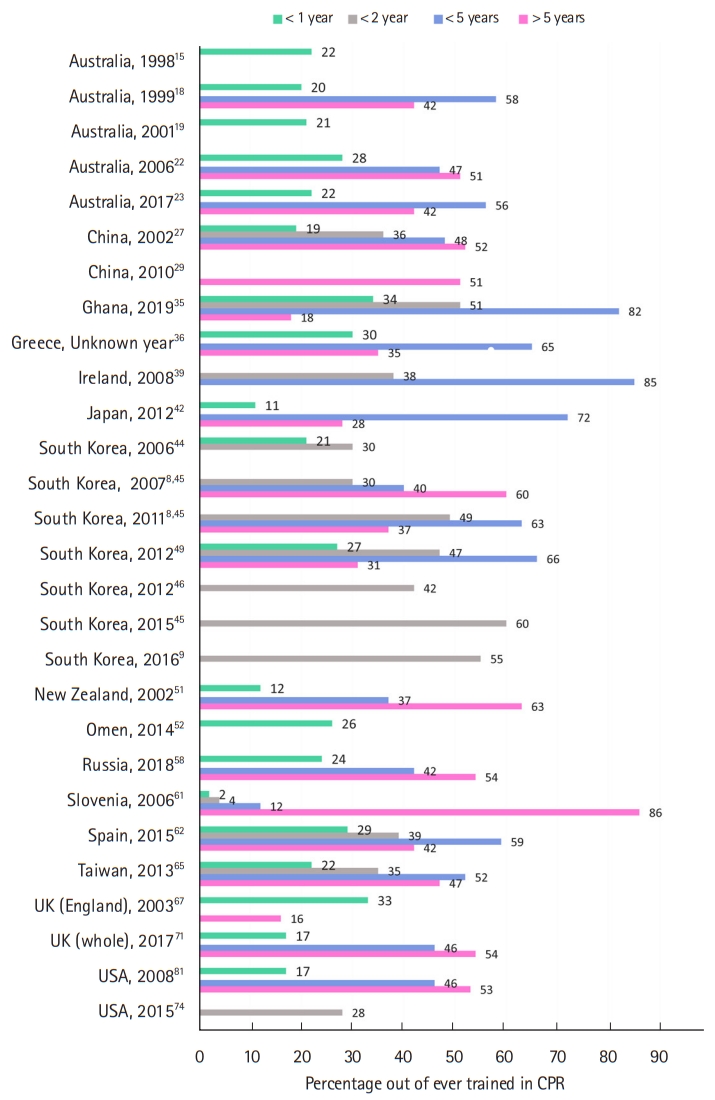

In terms of how recent the CPR training was 32.8% (n=20) of the studies reported percentage or number of people trained in CPR within the past 12 months (2%–34% of those ever trained in CPR; median [IQR], 22 [17.5–27.8]). Data were also provided for longer periods and are reported here as the percentage /number of people trained over the period for 2, 5 and more than 5 years, detailing the median and IQR. Thus, of the studies 23% reported the percentage of people trained within the past 2 years, the median and the IQR (4%–60%, 38.5 [30.0–49.5]), 29.5% of the studies reported the percentage/number of people trained within past 5 years (12%–85%, 54 [45.0–65.3]); and 31.1% (19) of the studies reported the percentage/number of people trained more than 5 years ago (16%–86%, 47.0 [35.0–54.0]) (Fig. 4) [8,9,15,18,19,22,23,27,29,35,36,39,42,44-46,49,51,52,58,61,62,65,67,71,74,81].

Several studies investigated the prevalence of CPR training in the same population and geography in different study periods. These studies were carried out in four countries: Australia, China, Japan, and South Korea.

In Australia, two cross-sectional telephone surveys were conducted in 2000 to 2001 [19] and 2016 [21,22] among residents of the state of Victoria (n=1,489 and 404, respectively), demonstrating an improvement in the CPR training prevalence. The percentage of people ever trained in CPR increased from 52% to 68%, and the percentage of those recently trained (within 1 year) increased from 21% to 28%.

In China, the general public of Hong Kong region was interviewed by telephone in 2002 (n=357) [27] and in 2010 (n=1,013) [28,29]. Based on the surveys, the overall prevalence of CPR training was 12% and 21%, respectively. Another telephone survey from Hong Kong (n=524) showed the CPR training rate of 23% but the year of the survey is unknown [32]. Additionally, two nation-wide surveys were carried out in China in 2014 (n=1,841; an online survey) [6] and 2018 to 2019 (n=99,186; a self-administered questionnaire) [30], reporting the percentages of people ever trained in CPR as 26 and 38, respectively.

In Japan, two country-wide surveys were conducted in 2006 (n=1,132; in-home face-to-face interviews) [40] and in 2012 (n=4,853; an online survey) [41,42]. These studies showed the community prevalence of ever being trained in CPR to be 35% and 49%, respectively.

For South Korea, Lee et al. [8] and Lee et al. [45] published results of three country-wide telephone surveys conducted in 2007 (n=1,029), 2011 (n=1,000), and 2015 (n=1,000). The reported percentages of ever being trained in CPR were 48, 38, and 51%, respectively, with the percentages of people trained within the previous 2 years reaching 30, 49, and 60%, respectively. Further, Ro et al. [46] presented the results of the nation-wide in-home face-toface interview conducted in 2012 (n=228,921), where the general prevalence of CPR training was reported as 27%, and the proportion of those trained within 2 years amounted to 42%. Finally, two in-home face-to-face surveys conducted in the Korean metropolitan city Daegu in 2012 (n=1,000) [9,47,49] and 2016 (n=1,141) [9,47] demonstrated an increase in prevalence of ever being trained in CPR (from 36% to 55%) and in the proportion of laypeople trained within 2 years (from 47% to 55%).

Factors associated with receiving CPR trainingThirty of 61 eligible studies (49.2%) investigated the association of participants’ sociodemographic characteristics with being previously trained in CPR. Based on a univariate or a multivariate analysis, prior experience of CPR training was confirmed to be associated with (excluding factors evaluated on a single occasion): age: younger (n=18 studies) or middle age (n=5) vs. older age; gender: man (n =9), woman (n =2), or not associated (n=12); race, ethnicity or country of birth (n=5), or not associated (n=1); educational level: higher (n=17), or not associated (n=1); socioeconomic status: higher (n=2), or not associated (n=1); income: higher (n=5), or not associated (n=3); employment status or occupation: employed/students (n=6), full-time/part-time work (n=2), working in a medical field (health-related, healthcare providers) (n=3), office workers or skilled workers (n=1), professional, managerial, and non-manual occupations (n=2), military conscripts (n=1), or not associated with employment status (n =1); marital status: non-married vs. married (n=1), never been married (n=2), married or never been married vs. separated or divorced (n=1), married vs. single, divorced or widowed (n=1), married or living as married (n=1); place of residence (urban/rural): urban (n=1), rural (n=1), or not associated (n=2); witnessed a cardiac arrest or a collapsed person (n=3), or not associated (n=1); member of a household (cohabiting family member) with heart disease or cardiovascular disease: positive association (n=1), negative association (n=1), or not associated (n=2); diseases in personal medical history: negative association (n=1), or not associated (n=1).

Willingness to be trainedSixteen studies (26.2%) evaluated the willingness of laypeople to be trained in (to learn) CPR. Of these, 12 studies reported the proportions of persons willing to be trained out of all the survey respondents (ranging from 52% to 96%); four studies asked this question of non-trained respondents only, and received positive responses from 42% to 73% respondents (Fig. 5) [23,30,31,34,35,38,45,53-55,58,62,64,69].

DISCUSSIONThis scoping review investigated the international evidence from the population-based surveys reporting the prevalence of CPR training among the general public over the last 20 years. The review reveals the occurrence and geographic distribution of the studies, clarifies the study design and the conduct of the research, identifies the knowledge gaps, and may inform future systematic reviews on the topic. The findings may be utilized by national and international authorities when planning public health initiatives directed at improving bystander CPR rates and increasing the survival rates after OHCA.

We found that studies of CPR training prevalence among the general public are occasional. For the past two decades, only 61 published studies were revealed. The studies were conducted in 29 countries, which amounts to about one seventh of the world’s sovereign states. No data on CPR training prevalence is available for low-income countries and only two studies were carried out in lower middle-income countries (Ghana and India). The surveys were most commonly performed in South Korea (8) and the USA (8), followed by China (7), Australia (6), the UK (4), Japan (3), Oman (2), and Spain (2). In the other 21 countries the studies were only conducted once. It is noteworthy that although the surveys were more common in countries with higher income economies, our search did not reveal any eligible studies for approximately 75% of the high-income countries and 89% of the countries with upper middle-income economies. Most surveys were carried out at a subnational level, and may not be considered as representative of the whole country. Furthermore, the majority of studies were conducted at a single point in time, and only a few surveys were repeated in the same population to show the dynamics of CPR training prevalence in a particular geographic area. Generally, the lack of studies suggests lack of measurement and monitoring of community CPR training in most countries, that in turn may suggest insufficient regard being given to the problem of OHCA from the national governments and healthcare agencies.

Another important finding is that the studies demonstrated significant methodological heterogeneity in the study design, sampling methods, data gathering methods, and participant selection criteria. Whereas the choice of the survey design largely depends on availability of certain modes of data gathering and their cost for the researcher, clearly these methodological differences may introduce diverse and pronounced biases inherent to non-standardized population-based surveys thus limiting comparability of the survey results. Many surveys had low response rates that might have led to non-response biases affecting the representativeness of the data. Further, in a number of cases the description of key methodological aspects was lacking in the full-text papers, preventing clear conclusions on the appropriateness of the study design used to achieve the aims of the study.

In order to improve the methodological consistency and comparability of future studies, it is advisable to develop international guidelines on survey methodology and uniform reporting of data on public CPR training practices. Following the Utstein style, the guidelines could be jointly developed by the recognized resuscitation societies to include uniform terms, definitions, methods, and a template for standardized reporting of survey results. The guidelines could serve as a valuable driver for supporting resuscitation research and in improving public health internationally. The incorporation of questions concerning CPR training into well-designed national public surveys could assist in obtaining reliable surveillance data on a regular basis.

Although pronounced methodological differences prohibit direct comparison of the presented results, the data demonstrate overall trends in the prevalence of CPR training among the general public. The huge variation in the CPR training rates (3%–79%) could be attributed to complex factors, including real disparities in existing practices of community resuscitation training between countries and regions, as well as differences in study design, research quality and reporting. Whereas the global prevalence of CPR training around 40% seem to be relatively high [11,25], it is definitely far from sufficient. Most studies were conducted in developed countries, where extensive campaigns are organized to engage the public and encourage CPR training [8,9]. Countries with high-income economies demonstrated more than double the median prevalence of CPR training when compared with the upper middle-income countries. The difference is anticipated to be much more pronounced in comparison with lower middle-income and low-income countries where public CPR training initiatives seldom occur [82], but where the mortality rate from non-communicable diseases continues to increase dramatically.

The proportion of people with recent CPR training was generally low and did not exceed 34% trained within one year across the studies, indicating the need to promote refresher training in resuscitation around the globe. Recent CPR training is a valuable indicator of the effectiveness of community resuscitation education effectiveness.

However, recency of CPR training was reported rarely and nonuniformly, once again suggesting the need for the international consensus in this matter.

All studies reporting the prevalence of CPR training in particular geographic areas at different time points, which were conducted in Australia [19,21,22], China [6,27-30], Japan [40-42] and South Korea [8,9,45-47,49], demonstrated an improvement in the general rates of resuscitation training and the rates of recent CPR training over time. Some of the papers discuss factors which may have contributed to the positive dynamics. For the Australian state of Victoria [22] and for Hong Kong [29], first-aid training in the workplace appeared to be one of the drivers for the increase in the proportion of CPR-trained individuals. In South Korea, the increase in the percentage of people ever trained and those recently trained in CPR, was related to a complex of major changes in public resuscitation training-related national practices, including the establishment of the national public CPR program, public advertising campaigns, enactment of a Good Samaritan law, and legislation for mandatory CPR training at school [8,9].

Besides the resuscitation training prevalence, some studies investigated associations between respondents’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and previous CPR training, reasons for not being trained in CPR, sources of resuscitation training, and willingness to get trained in CPR. Although important for understanding community CPR education practices and informing further improvements, these findings were reported by a minority of studies, and in a heterogeneous manner. Age, gender, educational level, and employment status/occupation were most commonly evaluated as potential determinants of previous resuscitation training. Younger age and higher level of education were consistently reported to be associated with a higher probability of ever being trained in CPR in different countries. Consequently, involvement of older people and those who have lower education level into community resuscitation training constitutes an international objective.

The most frequently reported reasons for not being trained in CPR generally fell into two categories: (1) low awareness and motivation to go for training (e.g., “never thought about it”, lack of concern, lack of time) and (2) low availability of CPR training (“do not know where to take the training”). This emphasizes the need for raising awareness of cardiac arrest and CPR training for laypeople, introducing mandatory CPR education and increasing access to alternative methods of training, including distance learning and blended learning approaches [7] worldwide.

The main sources of CPR training were generally similar across the countries, but varied in their order of prevalence. Most commonly, people were receiving training in educational institutions (school, college, and university), at workplace or from recognized providers (e.g., The Red Cross or emergency medical services). For South Korea, training through military/reserve forces was reported as the most common source before 2012 [8], with the subsequent shift towards the most prevalent training occurring at school [9].

The reported proportions of people being interested in attending CPR training varied over a wide range, but generally was no less than 50% of respondents who declared their willingness to undertake the training. These findings reveal a large potential for increasing the number of lay rescuers internationally.

This review has limitations. The scoping nature of the review prevented us from performing a systematic quality appraisal of the studies. Owing to the differences in survey design, methods, target populations, and reporting, as well as commonly encountered lack of relevant information on the methodologies used, the findings should be interpreted cautiously. Despite the comprehensive search for publications, it is possible that some eligible papers were not included due to the limitations of the search strategy, particularly those published in languages other than English and not indexed in the major bibliographic databases. For non-English articles (n=4), we analyzed English-language abstracts and tables only; thus, relevant data might have been omitted for the respective studies. Further, not all research gets published in scientific literature, and therefore the results of this review may not be representative of all the studies that have been conducted to investigate the prevalence of community CPR training. Finally, the prevalence rates of resuscitation training should not be interpreted as an equivalent of quality or effectiveness of public CPR training in the respective countries.

CONCLUSIONIn summary, this review has shown that studies investigating the prevalence of CPR training among the general public are few around the globe. Nothing is known about existing community resuscitation education coverage for the vast majority of countries of the world, and for most surveys the findings are not generalizable to a whole country population. Based on the available evidence from 29 countries, the global prevalence of CPR training is around 40% with obviously higher training rates in countries with higher income economies. Whereas some countries definitely reveal an increase in CPR training prevalence over time; there is an apparent need to further improve public awareness and education on resuscitation internationally. The review also revealed that studies are highly heterogeneous in survey designs, methods, and reporting patterns, making it difficult to interpret and compare findings. There is a need to develop international consensus guidelines on a standardized survey methodology and reporting of data on CPR training practices in order to enhance the consistency and the availability of resuscitation training monitoring, to guide CPR education processes and improve survival from cardiac arrest worldwide.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALSupplementary Tables are available from: https://doi.org/10.15441/ceem.21.066.

Supplementary Table 2.Characteristics of studies included in the review (n=61) Supplementary Table 3.Prevalence of CPR training (percentage of persons ever trained) by country, territorial level and year of survey REFERENCES1. Yan S, Gan Y, Jiang N, et al. The global survival rate among adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2020; 24:61.

2. Song J, Guo W, Lu X, Kang X, Song Y, Gong D. The effect of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation on the survival of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2018; 26:86.

3. Tanaka H, Ong MEH, Siddiqui FJ, et al. Modifiable factors associated with survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the pan-Asian resuscitation outcomes study. Ann Emerg Med 2018; 71:608-17.

4. Grasner JT, Wnent J, Herlitz J, et al. Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Europe: results of the EuReCa TWO study. Resuscitation 2020; 148:218-26.

5. Ong ME, Quah JL, Ho AF, et al. National population based survey on the prevalence of first aid, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillator skills in Singapore. Resuscitation 2013; 84:1633-6.

6. Chen M, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Public knowledge and attitudes towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in China. Biomed Res Int 2017; 2017:3250485.

7. Greif R, Lockey AS, Conaghan P, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 10. Education and implementation of resuscitation. Resuscitation 2015; 95:288-301.

8. Lee MJ, Hwang SO, Cha KC, Cho GC, Yang HJ, Rho TH. Influence of nationwide policy on citizens’ awareness and willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2013; 84:889-94.

9. Moon S, Ryoo HW, Ahn JY, et al. A 5-year change of knowledge and willingness by sampled respondents to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a metropolitan city. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0211804.

10. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169:467-73.

11. Duber HC, McNellan CR, Wollum A, et al. Public knowledge of cardiovascular disease and response to acute cardiac events in three cities in China and India. Heart 2018; 104:67-72.

12. List of sovereign states [Internet]. Wikipedia. 2021 [cited 2021 Jan 13]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_sovereign_states.

13. World Bank. Data: World Bank country and lending groups [Internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2020. [cited 2021 Jan 13]. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-andlending-groups.

14. Clark MJ, Enraght-Moony E, Balanda KP, Lynch M, Tighe T, FitzGerald G. Knowledge of the national emergency telephone number and prevalence and characteristics of those trained in CPR in Queensland: baseline information for targeted training interventions. Resuscitation 2002; 53:63-9.

15. Johnston TC, Clark MJ, Dingle GA, FitzGerald G. Factors influencing Queenslanders’ willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2003; 56:67-75.

16. Johnston TC, Clark MJ, Dingle GA, Sanders EL. Levels of cardiac knowledge and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training among older people in Queensland. Australas J Ageing 2004; 23:91-6.

17. Jelinek GA, Gennat H, Celenza T, O’Brien D, Jacobs I, Lynch D. Community attitudes towards performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Western Australia. Resuscitation 2001; 51:239-46.

18. Celenza T, Gennat HC, O’Brien D, Jacobs IG, Lynch DM, Jelinek GA. Community competence in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2002; 55:157-65.

19. Smith KL, Cameron PA, Meyer AD, McNeil JJ. Is the public equipped to act in out of hospital cardiac emergencies? Emerg Med J 2003; 20:85-7.

20. Dwyer T. Psychological factors inhibit family members’ confidence to initiate CPR. Prehosp Emerg Care 2008; 12:157-61.

21. Bray JE, Straney L, Smith K, et al. Regions with low rates of bystander CPR also have lower rates of residents with CPR training: a telephone survey of residents in Victoria, Australia. Circulation 2016; 134(Suppl 1):A16174.

22. Bray JE, Smith K, Case R, Cartledge S, Straney L, Finn J. Public cardiopulmonary resuscitation training rates and awareness of hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a cross-sectional survey of Victorians. Emerg Med Australas 2017; 29:158-64.

23. Cartledge S, Saxton D, Finn J, Bray JE. Australia’s awareness of cardiac arrest and rates of CPR training: results from the Heart Foundation’s HeartWatch survey. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e033722.

24. Scavee C, Scavee V, Marchandise S, et al. Is the general population ready to use an automatic external defibrillator? Heart Rhythm 2011; 8(Suppl 1):S209.

25. Bartlett ES, Flor LS, Medeiros DS, et al. Public knowledge of cardiovascular disease and response to acute cardiac events in three municipalities in Brazil. Open Heart 2020; 7:e001322.

26. Cheskes L, Morrison LJ, Beaton D, Parsons J, Dainty KN. Are Canadians more willing to provide chest-compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)?: a nation-wide public survey. CJEM 2016; 18:253-63.

27. Cheung BM, Ho C, Kou KO, et al. Knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among the public in Hong Kong: telephone questionnaire survey. Hong Kong Med J 2003; 9:323-8.

28. Hung MS, Lui JC, Chair SY, Lee DT, Shiu IY. A telephone survey on the attitude and knowledge of the Hong Kong public towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Int J Cardiol 2011; 147:S6-7.

29. Chair SY, Hung MS, Lui JC, Lee DT, Shiu IY, Choi KC. Public knowledge and attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Hong Kong: telephone survey. Hong Kong Med J 2014; 20:126-33.

30. Yan S, Gan Y, Wang R, Song X, Zhou N, Lv C. Willingness to attend cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and the associated factors among adults in China. Crit Care 2020; 24:457.

31. Yanjin L, Jing W, Fuqin L. Willingness towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and implementation in community residents and its influencing factors. J Nurs Sci 2012; 5.

32. Chan K, Chan NY. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation awareness and automated external defibrillator distribution survey in Hong Kong. J Hong Kong Coll Cardiol 2016; 24:34.

33. Schmid KM, Mould-Millman NK, Hammes A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to community CPR education in San Jose, Costa Rica. Acad Emerg Med 2015; 22(Suppl 1):S293.

34. Schmid KM, Mould-Millman NK, Hammes A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to community CPR education in San Jose, Costa Rica. Prehosp Disaster Med 2016; 31:509-15.

35. Anto-Ocrah M, Maxwell N, Cushman J, et al. Public knowledge and attitudes towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in Ghana, West Africa. Int J Emerg Med 2020; 13:29.

36. Hatzakis KD, Kritsotakis EI, Karadimitri S, Sikioti T, Androulaki ZD. Community cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in Greece. Res Nurs Health 2008; 31:165-71.

37. Arnar DO, Gizurarson S, Baldursson J. Attitude of the Icelandic population towards performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation on strangers in the pre-hospital setting. Laeknabladid 2001; 87:777-80.

38. Pranata R, Wiharja W, Fatah A, Yamin M, Lukito AA. General population’s eagerness and knowledge regarding basic life support: a community based study in Jakarta, Indonesia. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2020; 8:567-9.

39. Jennings S, Hara TO, Cavanagh B, Bennett K. A national survey of prevalence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and knowledge of the emergency number in Ireland. Resuscitation 2009; 80:1039-42.

40. Kuramoto N, Morimoto T, Kubota Y, et al. Public perception of and willingness to perform bystander CPR in Japan. Resuscitation 2008; 79:475-81.

41. Sasaki M, Yasunaga H, Ishikawa H, Kiuchi T, Sakamoto T, Marukawa S. Factors affecting people’s hesitation or motivation to resuscitate out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients: multilevel analysis in Japan. Resuscitation 2012; 83(Suppl 1):E38-9.

42. Sasaki M, Ishikawa H, Kiuchi T, Sakamoto T, Marukawa S. Factors affecting layperson confidence in performing resuscitation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients in Japan. Acute Med Surg 2015; 2:183-9.

43. Otani T, Ohshimo S, Shokawa T, et al. A survey on laypersons’ willingness in performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care 2011; 15:P295.

44. Lee MJ, Park KN, Kim H, Shin JH, Yang HJ, Rho TH. Analysis of factors contributing to reluctance and attitude toward cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the community. J Korean Soc Emerg Med 2008; 19:31-6.

45. Lee YK, Nho TH, Park YS, et al. Enhanced strategies through national tri-temporal analysis of public capacity prepared for laypersons’ cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Korean Soc Emerg Med 2016; 27:549-55.

46. Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Hong SO, Kim YT, Cho SI. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation training experience and self-efficacy of age and gender group: a nationwide community survey. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34:1331-7.

47. Moon S, Ryoo H, Lee D, Kim JH, Ryu HW. A 5year comparison of public recognition and willingness to perform bystander CPR in a metropolitan city. BMJ Open 2017; 7(Suppl 3):A15.

48. Kang KH, Yang HJ, Lee G, et al. Predictors of cardiopulmonary resuscitation education for layperson. J Korean Soc Emerg Med 2006; 17:539-44.

49. Son JW, Ryoo HW, Moon S, et al. Association between public cardiopulmonary resuscitation education and the willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a metropolitan citywide survey. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2017; 4:80-7.

50. Caruana E, Micallef S, Boffa MM, et al. Training the public in basic life support: are we making progress? Resuscitation 2013; 84(Suppl 1):S19-20.

51. Larsen P, Pearson J, Galletly D. Knowledge and attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the community. N Z Med J 2004; 117:U870.

52. Alshaqsi S, Alwahaibi K, Alrisi A. Wasted potential: awareness of basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the Sultanate of Oman: a cross-sectional national survey. J Emerg Med Int Care 2015; 1:105.

53. Al-Riyami H, Al-Hinai A, Nadar S. Attitudes towards basic life support among the general public in Oman. Indian Heart J 2019; 71(Suppl 1):S42.

54. Rasmus A, Czekajlo MS. A national survey of the Polish population’s cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge. Eur J Emerg Med 2000; 7:39-43.

55. Dixe Mdos A, Gomes JC. Knowledge of the Portuguese population on basic life support and availability to attend training. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2015; 49:640-9.

56. Birkun A, Kosova Y. Prevalence of and public attitudes to cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in the Crimea. Resuscitation 2018; 130(Suppl 1):E64.

57. Birkun AA, Kosova YA. Public opinion on community basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation training: a survey of inhabitants of the Crimean Peninsula. Russian Sklifosovsky J Emerg Med Care 2018; 7:311-8.

58. Birkun A, Kosova Y. Social attitude and willingness to attend cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and perform resuscitation in the Crimea. World J Emerg Med 2018; 9:237-48.

59. Qara FJ, Alsulimani LK, Fakeeh MM, Bokhary DH. Knowledge of nonmedical individuals about cardiopulmonary resuscitation in case of cardiac arrest: a cross-sectional study in the population of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Med Int 2019; 2019:3686202.

60. Quah JL, Ong ME, Chan MF, et al. Prevalence of first aid, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillator skills in Singapore. Proc Singap Healthc 2012; 21(Suppl 1):S148.

61. Rajapakse R, Noc M, Kersnik J. Public knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Republic of Slovenia. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2010; 122:667-72.

62. Ballesteros-Pena S, Fernandez-Aedo I, Perez-Urdiales I, Garcia-Azpiazu Z, Unanue-Arza S. Knowledge and attitudes of citizens in the Basque Country (Spain) towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automatic external defibrillators. Med Intensiva 2016; 40:75-83.

63. Rafecas Ventosa A, Ruiz-Rodriguez JC, Lidon RM, et al. General knowledge about cardiac arrest and skills in basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a population study. Eur Heart J 2017; 38(Suppl 1):ehx502; P2732.

64. Axelsson AB, Herlitz J, Holmberg S, Thoren AB. A nationwide survey of CPR training in Sweden: foreign born and unemployed are not reached by training programmes. Resuscitation 2006; 70:90-7.

65. Pei-Chuan Huang E, Chiang WC, Hsieh MJ, et al. Public knowledge, attitudes and willingness regarding bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a nationwide survey in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2019; 118:572-81.

66. Ozbilgin S, Akan M, Hanci V, Aygun C, Kuvaki B. Evaluation of public awareness, knowledge and attitudes about cardiopulmonary resuscitation: report of Izmir. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim 2015; 43:396-405.

67. Donohoe RT, Haefeli K, Moore F. Public perceptions and experiences of myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest and CPR in London. Resuscitation 2006; 71:70-9.

68. Brooks B, Chan S, Lander P, Adamson R, Hodgetts GA, Deakin CD. Public knowledge and confidence in the use of public access defibrillation. Heart 2015; 101:967-71.

69. Dobbie F, MacKintosh AM, Clegg G, Stirzaker R, Bauld L. Attitudes towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Results from a cross-sectional general population survey. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0193391.

70. Hawkes C, Booth S, Brown T, et al. Attitudes to CPR and public access defibrillation: a survey of the UK public. Resuscitation 2017; 118(Suppl 1):E39.

71. Hawkes CA, Brown TP, Booth S, et al. Attitudes to cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillator use: a survey of UK adults in 2017. J Am Heart Assoc 2019; 8:e008267.

72. Barnhart JM, Cohen O, Kramer HM, Wilkins CM, Wylie-Rosett J. Awareness of heart attack symptoms and lifesaving actions among New York City area residents. J Urban Health 2005; 82:207-15.

73. Coons SJ, Guy MC. Performing bystander CPR for sudden cardiac arrest: behavioral intentions among the general adult population in Arizona. Resuscitation 2009; 80:334-40.

74. Blewer AL, Ibrahim SA, Leary M, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training disparities in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6:e006124.

75. Blewer AL. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: training, delivery, and measurement error; [Dissertation]; Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 2018.

76. Petruncio LM, French DM, Jauch EC. Public CPR and AED knowledge: an opportunity for educational outreach in South Carolina. South Med J 2018; 111:349-52.

77. Fratta KA, Bouland AJ, Vesselinov R, et al. Evaluating barriers to community CPR education. Am J Emerg Med 2020; 38:603-9.

78. Knapp B, Lang J, MacEachern PB, Harris B, Stoner J. Awareness and perceived barriers to performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a community with a low bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation prevalence. Acad Emerg Med 2018; 25(Suppl 1):S58.

79. Blewer AL, Leary M, Ikeda D, Becker LB, Abella BS. The majority of laypersons trained in CPR do not maintain current certification or training. Circulation 2015; 132(Suppl 3):A16236.

80. Murray AD, McGovern SK, Leary M, Abella BS, Blewer AL. Assessing the relationship between neighborhood social capital and CPR training prevalence. Circulation 2016; 134(Suppl 1):A16975.

Fig. 2.Geographic distribution of surveys reporting prevalence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training among the general public. Numbers indicate quantity of surveys per country.

Fig. 3.Prevalence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training by country (percentage of survey respondents ever trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation).

Fig. 4.Percentages of lay people trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), categorized by time since last training (percentage out of ever trained in CPR).

Table 1.Respondents’ three main reasons for not being trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Table 2.Respondents’ three main sources of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||